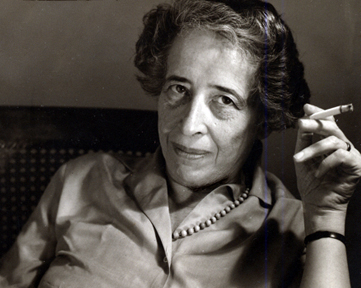

Adolph Eichmann was supposed to be this vile evil Nazi monster who personally sent 4.5-6 million European Jews to the death camps. Instead, Hannah Arendt described him as a normal man, unimportant, stupid, uninteresting person, an imbecile. Arendt covered Eichmann’s 1961 trial in Israel. Her observations were published in the New Yorker. From the moment she wrote she was vilified as anti-Semitic. Rabbis denounced her from the pulpit. Hannah Arendt was a former Zionist German Jew (d 1975). She was a philosopher. Arendt was attacked (and still is I hear) by Jews for “normalizing Eichmann” while flippantly attacking the Jewish leadership during World War II. She asked why didn’t the Jews fight back? She suggested the Jewish leadership (the Judenrate) were unwittingly complicit with the Nazis, providing names and locations of Jews, handing over keys to Aryans to move into abandoned apartments, and propagating the story that the Jews were simply being relocated to eastern cities – instead of being sent off to death camps.

But to the point of “banality of evil” here is what she meant

…only good has any depth. Good can be radical; evil can never be radical, it can only be extreme, for it possesses neither depth nor any demonic dimension yet and this is its horror! – it can spread like a fungus over the surface of the earth and lay waste the entire world. Evil comes from a failure to think. It defies thought for as soon as thought tries to engage itself with evil and examine the premises and principles from which it originates, it is frustrated because it finds nothing there. That is the banality of evil. Hannah Arendt, Eichmann In Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil, (Kindle location 203).

Arendt’s thoughts on the subjects of totalitarianism and evil are relevant today. I have noticed a type of “banality of good” or rather a banality of idealism. Progressives – both secular and Christian – are intolerant of any thought that is not their own. This idealism is actually a strong positioned moralism, if not an intolerant liberal fundamentalism. I believe it comes across “banal” because it cannot “engage itself” with goodness. This is true of all idealistic moral fundamentalism. Think for a moment of the deceased Fred Phelps and the Westboro Baptist Church in Topeka Kansas. While it is easy to disagree with Phelps’ anti- gay position, his position was a moral position – an intolerant, judgmental, and righteous stance. Phelps did not call it hateful. We do. He called it “good.”

Modern Progressive political worldview (secular humanism and transcendent/faith/traditional – Charles Taylor’s categories) shows the shift from a) personal sin but a pervasive social moral ambivalence to b) cultural sin and a sinless but “unhealthy” therapeutic self. In other words, everyone agrees that global warming is evil. But each of us keeps driving our cars guilt-free. “It’s not MY sin, global warming is the world’s sin.” Progressivism globalizes evil as anything deemed hegemony (white, male, affluent, Wall Street, European, military, Christian, etc). But Progressivism cannot engage itself – it cannot critique itself because it is a pervasive collective moral consciousness. It sounds like this: “If you are hip, up-to-date, and pluralistic and (wait for it) loving, then you accept all peoples.” Individuals feel empowered by the collective to attack any position or attitude that is not Progressive like them. This is mindless, banal good.

Back to Eichmann. (You’re not going to like my next thought.) Arendt pointed out that Eichmann was a simple idiot. He was not a monster (however, she still wanted him hanged for his crimes – she did not exonerate him). So if Eichmann did not mastermind the Holocaust, then what allowed it to happen? I believe average well-heeled, nice Germans allowed it to happen. A popular collective moral consciousness took over. This means that good normal people can do the most radical harm. I believe Gandhi first said this – “good men do the worst evil.” Arendt believes evil is impersonal, thoughtless, and mindless. Eichmann stated in his defense that he couldn’t be a doctor because he couldn’t stand the sight of blood. Arendt believed him. Eichmann said all he did was calculate how many people could fit into rail boxcars. That’s all he did. He was a mindless bureaucrat crunching numbers. On the first day of the trial, Arendt was flabbergasted that Eichmann has a cold and keep blowing his nose and coughing. He was just a man like anyone else. Banal.

Where am I going with this? Be very very careful Progressives. Would you take a job calculating just how many neo-Nazi skinheads can be shoved in a boxcar? Would you approve to have all sexual abusers castrated? Good can do great evil, yes? I will say this as way of solution: follow Jesus, with exactitude. The “love” of Progressivism is not the same as Jesus’ love. Progressivism’s love is not a better higher, evolved post-Christian love. Once Progressivism detaches from the cross and die-to-self it seeks power (which bureaucratizes) and calls this power a force for good. (Actually, I level this same power-seeking accusation at the Christian right these days, who in my opinion have stepped away from the cross and kenotic God, Phil 2:5-11.)

“Banality of good” might not fit within Hannah Arendt’s thoughts on good and evil. But she is not living in our day. I wish she did. I wonder what she would make of it all. I will continue to dig through her Eichmann In Jerusalem book. My apologies for writing so philosophically. This is where I live these days.

PS: if you want to understand Hannah Arendt more, then watch the 2013 drama, Hannah Arendt. There is also a 2016 documentary, Vita Activa: The Spirit of Hannah Arendt.